A celebrated album by Brazil’s greatest singer and greatest composer turns fifty in 2024, but many American fans of Antônio Carlos Jobim had to wait until the compact disc era to hear one of the artist’s finest records.

In 2001, a group of two-hundred Brazilian musicians, artists and journalists were asked to vote on Brazil’s all-time best song. “Águas de março,” by Antônio Carlos Jobim, won the largest votes, a beloved tune that many singers have covered since its debut in 1972. Named for the March rain that ends Brazil’s summer season, Jobim, who everyone called Tom, wrote Portuguese and English lyrics for the song, also known as “Waters of March.” This fascinating new song came as a departure for the composer, moving him farther away from the music that had made him famous. The signs of change were clear on Stone Flower and Tide, two jazz-influenced solo albums Jobim released in 1970. These two records came at the end of almost a decade Tom had spent recording and performing his music in the United States and being the familiar face for the bossa nova craze that swept through America in the 1960s.

Two years after Stone Flower and Tide, Tom returned to the U.S. to record an album of wondrous new music he simply titled Jobim. With “Águas de março” as the lead-off track, and the English-sung version closing the record, the 1973 self-titled album is split between passionate vocal songs and elaborate orchestrated pieces, all elegantly arranged by Jobim’s frequent recording partner Claus Ogerman. Urubu followed in 1976, and it uses a similar blueprint, with a full side devoted to a four-part suite of dynamic orchestration that’s best experienced as a whole. As much as these albums are progressive, Jobim and Urubu also brought the composer back to his past, before bossa nova, when the young arranger drew inspiration from classical composers he absorbed as a teenager. The early 1970s were a fruitful period for the composer, and between the release of Jobim and Urubu, he also lent a hand to a side project that, like those two albums, straddled his past with new musical trends of the period. An album with the Brazilian singer Elis Regina. The artist known as “Furacão” (“Hurricane”).

Elis Regina first recorded “Águas de março,” for her 1972 album Elis. With her husband, pianist César Camargo Mariano acting as musical director, Regina released three adventurous records between 1972 and 1974, all with the album title Elis. On these records, Regina introduced songs by a new generation of Brazilian songwriters who would later go on to have larger careers—Ivan Lins, and João Bosco, for example—along with songs by current superstars, mainly Milton Nascimento and Gilberto Gil. More than anything, the arrangements of the songs were modern for the time, using electric instruments that reflected the changing musical style of the early seventies. There were some songs by the old guard—Guilherme de Brito, Nelson Cavaquinho, Ary Barroso—which were also given updated treatments. “Águas de março” fit here also, a new song with a grand lyrical flair. Still, Elis and César had another project they longed to do. A complete album of Jobim songs, just like another record they mutually admired: Por Tôda Minha Vida by Lenita Bruno, originally released in 1959. The album featured songs Tom had written in the fifties with poet Vinicius de Moraes, all orchestrated by Bruno’s husband Léo Peracchi. A recording free of any bossa nova.

Back in 1954, Tom played piano in the evenings at the Clube da Chave in Copacabana. He had taught himself orchestration and had worked as an arranger at Continental Records and, at Brazil’s oldest label, Odeon. At Continental, he composed his first serious composition: Sinfonia do Rio de Janeiro, co-written with Billy Blanco, and the first record released under his own name. He now played piano to pay the rent, so he could spend his days composing. One evening at the club, Vinicius de Moraes asked Tom if he would be his songwriting partner for his new play, Orfeu da Conceição. The play became a hit and later made into the film Black Orpheus, which won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1960. Along with music for the play and the film, Tom and Vinicius wrote other popular songs, including one that changed music in Brazil forever. “Chega de saudade,” arranged by Jobim and performed by João Gilberto, is given the credit for introducing “the beat” of bossa nova. To say that the release of this record is monumental doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface. As author Ruy Castro explained in his terrific book Bossa Nova: “it was unknown at the time, but later it would be discovered that no other Brazilian record would awaken the desire in so many young people to sing, compose, or play an instrument, specifically, the guitar.” Jobim and Gilberto would make three albums together between 1959 and 1961 and the impact of these records launched the bossa nova movement in Brazil and beyond. Bossa nova soon spread to the United States, and Jobim, Gilberto and other Brazilian musicians traveled to New York in 1962 to perform their music at a concert at Carnegie Hall. After the show, most of the musicians returned home, but Jobim stayed behind to make his new records in America.

* * *

It began with a phone call in early 1974, when Tom and his family were living in Los Angeles. The call came from André Midani, President of Phonogram, with a request. The record company had gifted Elis Regina a trip to LA, in appreciation of her first decade with the label, and while visiting there she would record a new album using only the composer’s songs. Would Tom take part in the sessions? Jobim accepted, but he would only take a limited role, playing piano or guitar. Making an album with Regina seemed simple enough, and Tom probably felt assured that everything would be alright; the label had assigned his old friend Aloísio de Oliveira to oversee the project. And besides, with two of Brazil’s most famous artists working on a record together, everything should go smoothly. Shouldn’t it?

Tom and Elis didn’t always get on well. He first heard her sing in 1964, when she auditioned for a part in a recording for the musical Pobre Menina Rica, which Tom was writing arrangements for during one of his return trips to Brazil. The riff may have been because Tom selected singer Dulce Nunes for the part instead of Regina. And Jobim didn’t end up being on the record either, opting instead to turn the project over to another arranger to complete. The slight didn’t dampen Regina’s future—a year later, she earned first place at the TV Excelsior music festival, for her animated performance of the Edu Lobo/Vinicius de Moraes song “Arrastão.” With her arms flapping like a bird in flight and her voice extending to a thunderous volume, the “Hurricane” wooed the festival audience. The performance affected the young people of the television age, just as João Gilberto had done through radio and records six years earlier, and where a new class of musicians, such as Milton Nascimento and Ivan Lins, took their cue. It made Elis Regina a star. She continued to appear on TV, co-hosting the show O Fino da Bossa with singer Jair Rodrigues from 1965 to 1967 and Som Livre Exportação with Ivan Lins in 1971 and 1972. On her records, Regina delved into a variety of styles: samba, jazz, rock, and the country’s popular songs, labeled MPB in Brazil. And, of course, bossa nova.

Elis didn’t want her new LP with Tom to be a bossa nova record. She selected three songs from the Lenita Bruno album and later, with Tom’s suggestions, picked others that were mostly written in the 1950s. The label had high sales expectations for the new album, not only in Brazil but also in Japan, Europe and in South America. And TV Bandeirantes would be on hand to film the recording sessions for a television special. It would be the record event of 1974.

Things initially started out well. Tom met Elis, her son João, and César at the L.A. airport, greeting Regina with flower in hand. They went to Jobim’s home to discuss the album, and after Tom learned César planned to do the arrangements, the niceties ended. Mariano’s experience with writing arrangement had not been extensive. Despite any discomfort it brought, Tom immediately picked up the phone and began looking for another arranger. He preferred Claus Ogerman, but when he or any of Tom’s other choices were not available, Jobim had to settle for César Mariano. But not without some goading. The usually composed Jobim became a pest, calling Mariano several times a day as he worked on arrangements, voicing his objections throughout the sessions, and making numerous calls during the album mix. So much for a being a minor contributor.

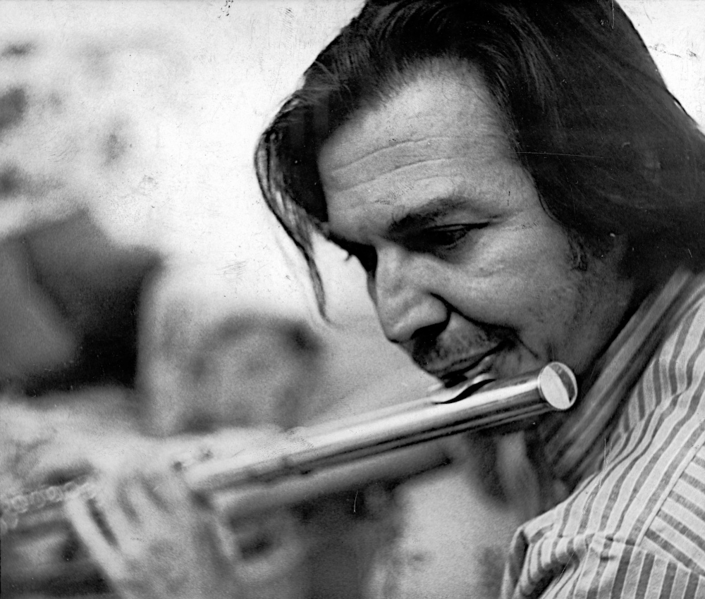

Before they needed her in the studio, Elis stayed away, visiting Disneyland and going on outings with João around the city. The atmosphere didn’t get any calmer when the tape started rolling. Tom protested against the “modernizing” of his songs, and especially didn’t like the use of electric guitar and an electric keyboard on some tracks. Regina, whose famous temper also earned her the nickname ”Pimentinha” (Pepper), stuck with the recording, frustrated with Tom but thrilled with the results they were achieving. For his part, César didn’t just lean on a contemporary sound; he wrote rich string arrangements that matched Jobim’s style. Tom plays piano, guitar and flute on the record, added his vocals to “Corcovado,” and “Soneto De Separação,” and provided his trademark wordless voice to “Inútil Paisagem.” The latter song, in particular, with Jobim playing a delicate piano accompaniment, could have only been created with the influence of Brazil’s greatest composer.

Best of all is Regina herself. Her vocals on Elis & Tom provide further proof of why she often called Brazil’s greatest singer. The care taken in her delivery for “Pois É,” “Só Tinha De Ser Com Você,” and “O Que Tinha De Ser” are just three examples of her stunning vocals on the album. Tom had suggested an English song—-they recorded “Bonita” but left it off the album, Regina insisting on only an all Portuguese language program. He also offered her a new song, the lovely “Ligia,” which hadn’t been on any record yet, but Regina turned it down, only wanting songs previously recorded. After completing the album, Tom publicly praised César Mariano for his arrangements on the Elis & Tom. And why wouldn’t he? It’s a masterpiece. A genuine work of beauty.

Sadly, Elis Regina wouldn’t live long enough to see the release of the album in the country where it was recorded. Just twenty-nine when Elis & Tom was completed, she would only live to age thirty-six, passing away in January 1982. Despite the label’s broad outlook for the album, Elis & Tom wouldn’t be released in the United States for fifteen years. Verve finally made it available for American audiences through a 1989 compact disc reissue. Jobim’s two “progressive” early-seventies solo records weren’t big sellers and he would complete his two decades of U.S. recordings with the 1980 album Terra Brasilis, a two-disc collection of remakes of many of his bossa nova hits. It would be his last album with Claus Ogerman.

In the last fourteen years of his life, Jobim recorded most of his new music in Brazil. He also formed Banda Nova, with family and friends, to tour the bossa nova songs he’s best known for. Elis & Tom is now a classic and considered one of Brazil’s best albums, ranked #11 by Rolling Stone on their 100 Greatest Brazilian Records list. Next year, Elis & Tom turns fifty. The album’s high point is Jobim and Regina’s duet on “Águas de março”—lively and fun, and still the best recording of the song ever. It kicks off the record, with the two singers playfully trading lines back and forth, Regina laughing, and adding vocal accents to the words. Even the backing piano has a skip in its step. The film crew captured the duet, and they shot a video for the song. Any bad blood between the two disappeared when it’s performance time. Huddled under a single microphone, they swing to the music, point and whistle, and ham it up for the camera. Just like two legends of Brazilian music only could.